All people could do was hope the nerds would fix it: the global panic over the millennium bug, 25 years on

Published 12/28/2024, Planes were going to drop out of the sky, nuclear reactors would explode. But then … nothing. What really happened with Y2K? People still disagree … By Tom Faber

Just before midnight on New Year’s Eve, 25 years ago, Queen Elizabeth II stepped off a private barge to arrive at London’s Millennium Dome for its grand opening ceremony. Dressed in a pumpkin-orange coat, she entered the venue with Prince Philip, taking her place alongside Tony and Cherie Blair and 12,000 guests to celebrate the dawn of a new millennium. At the stroke of midnight, Big Ben began to chime and 40 tonnes of fireworks were launched from 16 barges lined along the river. The crowd joined hands, preparing to sing Auld Lang Syne. For a few long moments, the Queen was neglected – she flapped her arms out like a toddler wanting to be lifted up, before Blair and Philip noticed her, took a hand each, and the singing began. A new century was born.

One politician who wasn’t in attendance at the glitzy celebration was Paddy Tipping, a Labour MP who spent the night in the Cabinet Office. Tipping was minister for the millennium bug. After 25 years, it might be hard to recall just how big a deal the bug – now more commonly called Y2K – felt then. But for the last few years of the 90s, the idea that computers would fail catastrophically as the clock ticked over into the year 2000 was near the top of the political agenda in the UK and the US. Here was a hi-tech threat people feared might topple social order, underlining humanity’s new dependence on technological systems most of us did not understand. Though there are no precise figures, it’s estimated that the cost of the global effort to prevent Y2K exceeded £300bn (£633bn today, accounting for inflation).

So Tipping spent the night at 70 Whitehall, among boxy grey computers and a small group of civil servants in communication with other world governments. “We watched the sun rise across the world,” he recalls, “first in Australia, New Zealand, right through Asia. There were no reports of any real problems. Come midnight, I was actually quite relaxed about things.” After a few hours, when it became clear disaster would not strike, he walked back across the bridge to his home in Lambeth. The streets were full of drunken revellers, the mood was joyous, and the world was resolutely not ending.

Y2K went down in history as a millennial damp squib, much like the dome itself, which is largely remembered for brazen corporate sponsorship, broken attractions and hour-long queues to spend a few minutes walking inside a giant human body. Curiously enough, to this day experts disagree over why nothing happened: did the world’s IT professionals unite to successfully avert an impending disaster? Or was it all a pointless panic and a colossal waste of money? And given that we live today in a society more reliant on complex technology than ever before, could something like this happen again?

Though the Y2K threat was voiced publicly as early as 1958, it became a common concern only after the publication of a 1993 article in Computerworld magazine by Canadian engineer Peter de Jager, apocalyptically headlined “Doomsday 2000”. The problem was simple. Most computers at the time stored dates as six-digit numbers, so 30 August 1991 would be 30/08/91. Using two digits for the year was never a problem during the 20th century, but on the first day of the new millennium, the date would read 01/01/00, and IT professionals were concerned computers would think it was 1 January 1900, rather than 2000, causing errors in their systems.

A common misconception is that the problem was a coding mistake, perhaps encouraged by widespread use of the word “bug”. In fact, storing years as two digits was a deliberate design compromise made by coders trying to save space in the days when every byte of hard drive storage cost serious money. Much of this early code was written decades earlier by programmers who never expected their software to still be in use in 2000.

The concern was that, as a result, computers might get the date wrong, leading to failures in everything from personal computers to those controlling financial markets, hospitals, air travel, military equipment and social infrastructure such as traffic lights or ventilation systems. People were afraid of “cascading faults”, where one system failing would knock out another like dominoes, perhaps compromising essential services such as the electric grid or running water.

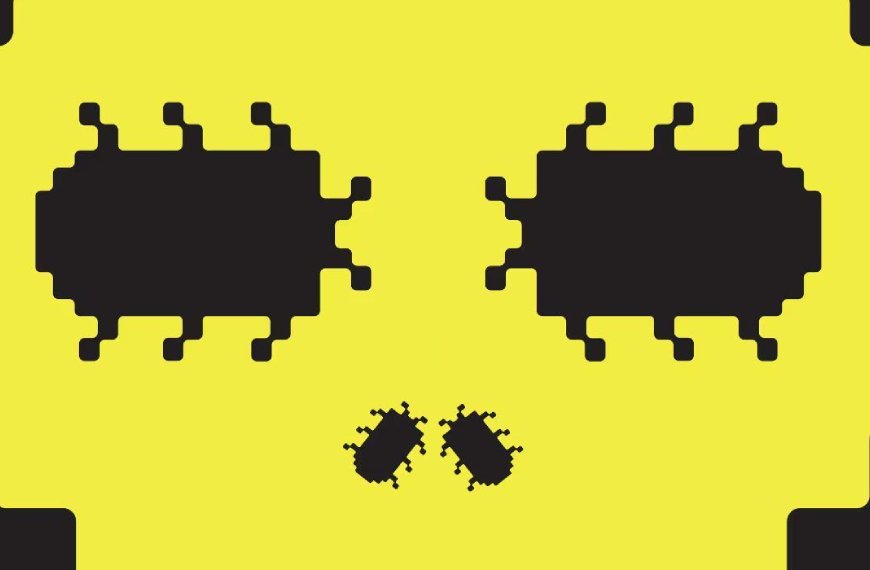

After a slow start, the UK began to take the threat seriously. In 1998, Blair warned in The Independent, “Ticking away inside many of our computers is a potential technical time bomb ... unless we act, the consequences of the Millennium Bug could be severe.” Others raised awareness in different ways, such as leader of the House of Commons Margaret Beckett, who was photographed cutting a Y2K bug-themed cake featuring the government’s official bug mascot, resembling a microchip with 10 legs and malevolent eyes, which was plastered across Y2K compliance brochures, pull-outs in newspapers and billboards that asked in bold type: “Are you sure you’ve done enough?”